Mikhail Khodorkovsky, former CEO of oil and gas company Yukos who has gone from being Russia’s richest man to its best-known prisoner (before we learned about Pussy Riot), and now its most famous émigré, recently announced his presidential ambitions. Given that in a country of 143.5 million there are no viable alternatives to the “national leader”, the thought of having Khodorkovsky as a candidate may appeal to the educated class. But is he really electable?

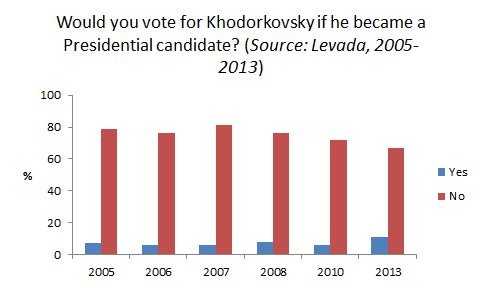

According to surveys by Levada Centre, most Russians are not ready to vote for Khodorkovsky. This graph shows that in the nine years between 2005 and 2013, only a very small share of respondents answered “yes” to this idea. And while the share of those who say “no” is less than it used to be, these people still qualify as the overwhelming majority.

Why are so many people unwilling to vote for Khodorkovsky? I will describe three factors that potentially make him unelectable and then reflect on why these factors may not be so important, after all:

1. Wealth. This is something that Americans will probably find hard to understand as in the US wealth is respected. In Russia it’s not and won’t be for a long time. As a former oligarch, Khodorkovsky is hard to sympathize with for an average Russian person. We know that Khodorkovsky has learned to live with less but this still may be an issue for many.

2. Criminal record. Khodorkovsky is known in the West as a political prisoner, but for many Russians he is just a criminal. Khodorkovky was sentenced for leading an organized criminal group that committed fraud, tax evasion, and misappropriation of funds. Several of his subordinates and colleagues also received lengthy prison sentences, and one of them, Alexey Pichugin, was given life sentence for murder. Also, according to Russian law, Khodorkovsky can’t take part in an election for at least another 10 years.

3. Ethnicity. This is perhaps the most controversial factor. A popular view voiced by Russian journalist V. Pozner is that since Khodorkovsky is Jewish, Russians are unlikely to vote for him. Indeed, anti-Semitism has traditionally been somewhat of a factor in Russian politics. Although they would not admit this publicly, many Russian politicians today could subscribe to this quote from L. Kaganovich (Stalin’s Commissar for Transportation): “Jews are always stirring up trouble because they are less dependend on a country’s tradition and they maintain bonds with their compatriots abroad.” (as quoted in this book, my translation). In Russia, as in some other post-Soviet states, the ethnic factor is routinely used to harass political opponents. For example, just this year Putin’s chief propagandist D. Kiselyov has reproached Putin’s critics for being ungrateful to Russia, hinting at their Jewish origin, and NTV, another propaganda channel, has claimed that Russian Jewish intellectuals who criticise Putin’s political agenda are “igniting anti-Semitism”. But how does that relate to an average Russian? Surveys by the Public Opinion Foundation (FOM) show that between 2005 and 2013, the share of Russians who didn’t have prejudices against Jews grew from 83% to 87%. In other words, very few Russians would admit explicitly that they have something against Jewish people. Of course, this is a sensitive question that not everybody is willing to answer openly. Also, we should consider that the conflict in Ukraine, tensions between Russia and the West, and the associated campaign against the “fifth column” have contributed to anti-Semitism. Recent monitoring of hate speech reveals that public anti-Semitism is on the rise, and the two examples mentioned above that anti-Semitic hints are becoming a normal part of the political discourse. Sure, this isn’t an official anti-Semitic campaign and hate speech hasn’t yet resulted in pogroms, but there’s always a time gap between speeches and actions. And if need be, Russian propagandists still have enough time to play the ethnic card to convince Russians that Khodorkovsky is to blame for Russia’s troubles.

Now that I’ve listed the three factors that make Khodorkovsky unelectable, I’ll try to explain why these factors may not be so important. To understand this, it makes sense to look at what Russians actually think of Khodorkovsky. I’ve collected here the results of several surveys by VCIOM, Levada Center, and FOM, and I think they show an interesting picture.

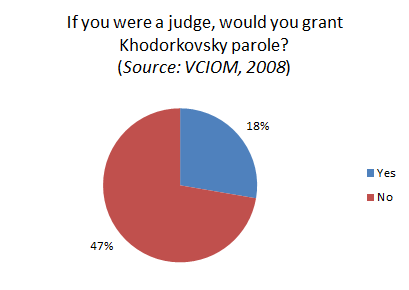

In 2008, after a second case against Yukos was opened, the majority of respondents of a Russia Public Opinion Research Center (VCIOM) poll believed that Khodorkovsky should stay in prison (35% of the respondents didn’t respond or were undecided):

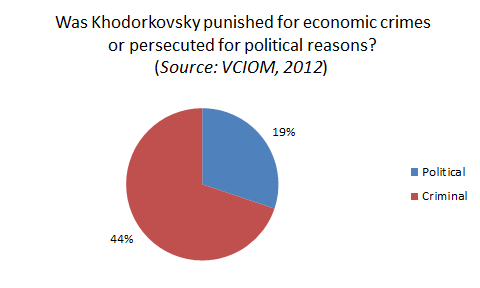

Did Russians support Khodorkovsky’s prison sentence because they were not aware of the political factors in his case? Perhaps they are more aware of that now? Well, according to a more recent VCIOM survey, in 2012 only 10% of Russians thought Khodorkovsky was a political prisoner. To see a fuller picture, let’s look at the answers to the question Khodorkovsky’s case is viewed controversially in Russia and other countries. Some think he was punished for the economic crimes that he had actually committed, while others are convinced that he is being persecuted for political reasons. Which position is more appropriate for you? from the same survey. We see that in 2012, twice as many Russians saw Khodorkovsky as a criminal than those who saw him as a political prisoner (again, over 35% didn’t respond or were undecided):

Interestingly, Levada Center tells us quite a different story. Let’s look at their surveys from 2010 until 2013, more specifically at responses to the question Why do you think Khodorkovsky is still in prison? We see that the share of those who thought Khodorkovsky was in prison due to political or personal reasons has grown significantly (although with fluctuations), and the share of those who thought he was in prison because he was a criminal has gone down (here, too, one can see that many didn’t, or couldn’t answer the question):

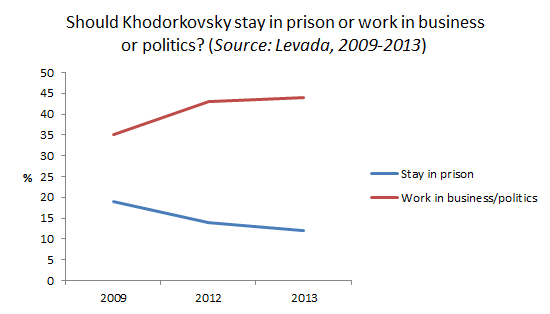

What this may indicate is that with time, Russians became more sympathetic to Khodorkovsky’s situation. Those who were aware of his situation, that is. Answers to another question from the same surveys Is it better for Russia that Khodorkovsky should stay in prison or work for the country’s benefit in business or politics? show that during five years (2009-2013) the share of people who wanted the former oligarch to stay in prison decreased and the share of those who wanted him to work in business or politics increased:

Finally, in December 2013, after Khodorkovsky’s unexpected release, FOM did a survey that included the question Do you see Khodorkovsky’s release as something positive or negative? You can see on this graph that while the share of positive responses was higher than that of negative ones, most respondents were really indifferent to Khodorkovsky’s release (again, many couldn’t answer the question) – and this, I think, points to something important:

It’s easy to see the contradictions between VCIOM, FOM and Levada results; VCIOM and FOM respondents were more likely to side with the government in Khodorkovky’s case compared to Levada respondents. But what these surveys have in common is this: many Russians are undecided. They don’t think anything of Khodorkovsky’s ethnicity, the reasons for his incarceration, or his wealth: they are a clean slate. Indeed, the share of respondents who are not following the developments in Khodorkovsky’s case is usually between 30% and 50%. Is it that people are not politically active? Is it that they have no access to this information through state-controlled media? Are they not interested? Well, whatever it is, this indicates that it may be possible to convince these undecided Russians that Khodorkovsky can represent their interests. But if these people had to choose, why would they choose Khodorkovsky over Putin?

It’s easy to see that Putin is selective in his responses to the electorate. When he became President, he had a largely pro-market, liberal agenda. Today he is defending government intervention. As a self-proclaimed Russian nationalist, he has appropriated a lot of his opponents’ conservative and nationalist rhetoric. But there is one thing that hasn’t changed much – Putin still lacks a social-democratic agenda. Indeed, as a populist he has contributed to the growth of budgetniki – people who depend on the state budget for their salaries and benefits, for their survival. However, he has all but ignored the gap between the rich and the poor. In 2012, Russia’s Gini index was 42.0 – better than the US but much worse than European countries or Canada. And as someone who strengthened executive power structures and undermined the already weak parliamentary and judicial systems, he is responsible for another gap – the gap between the state and its citizens. In a sense, Putin’s system is typical state capitalism, hostile to any kind of social democracy. Many Russians understand that, and that’s exactly why several years ago Alexey Navalny was able to build a successful public campaign against Putin, even with limited media exposure. Putin is a colossus with feet of clay.

As opposed to Putin, Khodorkovsky understands what most Russians need in the long term. He has admitted the mistakes he and other oligarchs made in the 1990s, during and after the first wave of Russia’s privatization. He has emphasized social equality and the importance of creating opportunities for the majority of Russians, not just for those who support the “national leader”. Importantly, he has been inside the notorious Russian prison system which has changed little since the GULAG years, aside from rapid commercialization. Khodorkovsky has seen, and thought about, things that other wealthy Russians haven’t even considered. In fact, today Khodorkovsky knows a lot more about Russia than Putin does – but also more than do most of his supporters. Judging by his speeches, he understands that Russians want a president who is moderately nationalistic and who is not confrontational but will protect Russia’s interests if necessary. They want a president who will discourage corruption but won’t promote unfettered capitalism. They want a president who will create business opportunities but not at the cost of dismantling the existing safety net. Putin is not that president. Can it be Khodorkovsky? Time will tell but a first, small step has just been made.